Beeronomics

While visiting our eldest daughter Jillian in Tacoma Washington last month, we visited her favorite Irish pub in town, Doyle’s Public House. While enjoying a pint (or two!) of Guinness, I

was reminded of a story I’ve told many friends and clients over the years while standing at the bar—one that’s equal parts economics lesson and clever pub parable.

Ten friends meet at the same pub every night on their way home from work, at 5 p.m. sharp.

They each order a Guinness, argue about politics and sports, and happily split the $100 bar tab based on their respective wealth. It’s a very progressive system that works well for them

because they are all friends, albeit each from very different means.

- The four poorest friends drink for free. The ten have been life-long buddies and want everyone to partake in a pint or two regardless if they can afford it!

- Based on their wealth and incomes, the remaining six friends split the tab as follows; the fifth fellow only has to pay $1 to join the crowd, the sixth man pays $3, the seventh $7, while the eighth and ninth are better off financially and happily pay $12 and $18 respectively.

- And the wealthiest of the ten friends happily pays the entire balance of the tab, $59.

Everyone’s happy. The Guinness flows. The bartender gets tipped. The system works well for everyone.

Until one night, the bartender announces a 20% discount on the gentlemen’s tab. “Tonight’s tab is only $80 boys,” he says, polishing a pint glass like he’s just triggered a fiscal policy debate.

Now the friends must decide how to split the $20 discount. The four who usually drink for free want their “fair share” of the $20 savings, yet they hadn’t paid anything into the tab to begin with. The middle earners argue they should each get at least couple of dollars off of their tabs,

even if it now means they pay nothing. The wealthy friend, who paid $59 the night before,

suggests he should get the bulk of the discount—after all, he’s the one who foots most of the bill every time the guys get together.

Maybe it was the Guinness, maybe it was their lack of understanding of how tax cuts actually work, but the conversation went sideways as the ten men argued over who should benefit from the $20 discount they received.

The wealthy friend finishes his pint, throws down his usual contribution to the bill, tips his hat, and walks out of the pub without nary a word to his friends.

The next night, only nine friends showed up to the pub. Their wealthiest friend decided to stay home tonight and not join the boys for a wee pint. The tab this evening is still $80, but now only

nine friends are available to split the bill.

Suddenly, the mood goes as flat as a stale pint of beer. The four who usually drink for free argue that they should still pay nothing, but the fifth guy now must pony up $10, the sixth mate

$17, the seventh gent $20, while the eighth pal pays $24, and the upper middle class ninth guy must pick up the tab’s balance of $29. But now the mood has soured. The Guinness tastes bitter. The bartender wonders if he should’ve just kept the discount scheme to himself.

No one is happy. The five middle-class guys end up having to each pay more and foot the entire bill, while the bottom four buddies are unscathed. The wealthy friend is sitting home (alone)

sipping on a Macallan 25-year sherry oak single malt from his private stock, impervious to the drama.

This story is a masterclass in economic behavior. It’s not about whether progressive taxation is good or bad—it’s about incentives. When the mechanics of the financial system change, people

respond. Sometimes rationally, sometimes emotionally, but always with consequences.

We’ve all seen this play out in real life. When capital gains tax rates rise, investors hold onto assets longer, reducing liquidity. When corporate tax rates drop, companies may reinvest the

tax savings into the business, accelerating growth. When interest rates go down, the housing market becomes more affordable, and transactions abound. It’s all about the incentives. It just depends on who’s picking up the tab.

The market also incentivizes investors like us to strategically take risks when allocating our investment dollars. Where will we get the greatest risk adjusted return from our portfolios?

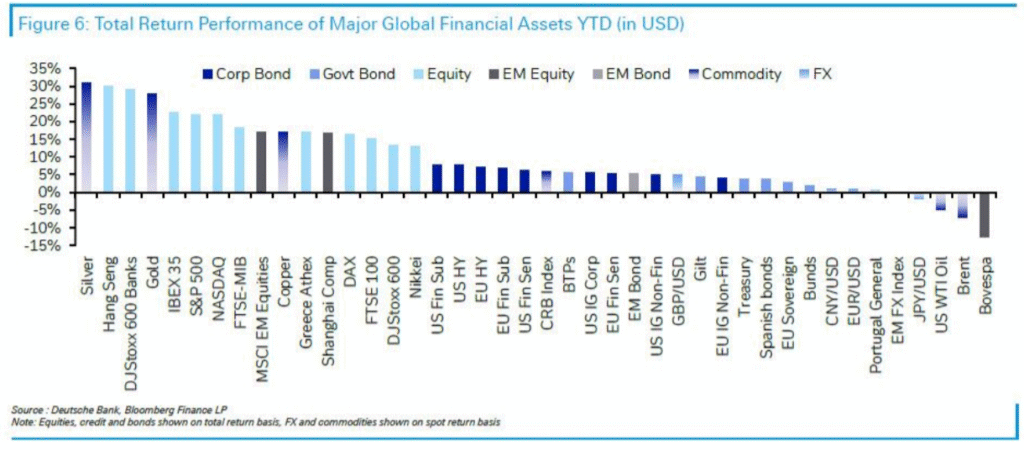

Well, so far year-to-date our “D.I.C.E.” strategy has continued to work out fairly well for everyone. As you will recall, we focus on Dividend payers, International equities, Cash & Commodities, and Emerging markets & industries. This chart below shows the best and worst performing sectors so far in 2025.

As you can see from this chart, silver & gold (in our D.I.C.E. commodity bucket) are the best performing assets Y-T-D, followed by international equities. Our dividend payers were represented above by banks and investment grade bonds. And finally, Emerging market equities were in the top ten performers as well. The 25/25/25/25 D.I.C.E. strategy is paying off, and many investors are starting to follow our lead. Here is a recent article in the Wall Street Journal showing how other finance professionals are focusing on the benefits of greater portfolio diversification than the traditional 60/40 split between stocks and bonds.

So, cheers to another quarter of thoughtful investing with behavioral insight over the economy, and hopefully, fewer arguments over the tab.

Sláinte,

Written by Jim Claire